Canadians Grapple with Distinguishing Truth from Falsehood in the Digital Age

The digital revolution has ushered in an era of unprecedented access to information, but this accessibility has also opened the floodgates to misinformation. A 2023 Statistics Canada survey revealed that over 40% of Canadians find it increasingly challenging to discern true news from fabricated content, a concern amplified by the fact that nearly three-quarters of Canadians encountered suspected false information online in the preceding year. This pervasive issue underscores the urgent need to understand the factors influencing how individuals engage with online information, particularly the behaviours of fact-checking and sharing unverified content. This article delves into the findings of a multivariate analysis exploring the demographic and socioeconomic influences on these crucial behaviours.

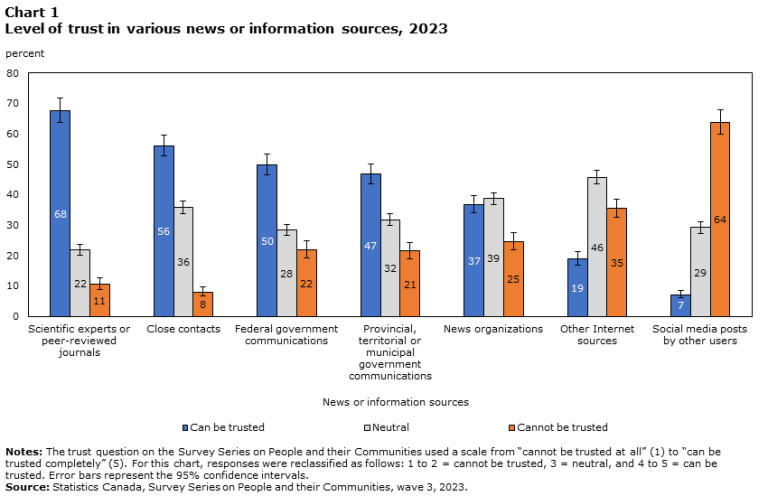

The study utilizes data from two Statistics Canada surveys: the Survey Series on People and their Communities (SSPC) and the Canadian Internet Use Survey (CIUS). The SSPC examined the likelihood of individuals verifying information accuracy, while the CIUS focused on the propensity to share unverified online content. A significant finding is the varying levels of trust Canadians place in different information sources. While social media has become a prevalent news source for many, it ranks among the least trusted. Scientific experts and peer-reviewed journals enjoy the highest levels of trust, followed by close personal contacts and the federal government. This disparity in trust levels highlights a potential connection between low trust in certain sources and the proliferation of misinformation online.

The SSPC revealed that over half of Canadians regularly fact-check news and information, while a small minority never do. Among those who don’t consistently fact-check, lack of interest or motivation is the most common reason. Regression analysis identified age and education as significant factors influencing fact-checking behaviour. Older individuals were less likely to verify information, potentially reflecting a preference for offline information sources. Conversely, higher education correlated with increased fact-checking. Interestingly, higher levels of concern about misinformation and typical use of expert sources also predicted a higher likelihood of fact-checking. This might suggest that individuals already inclined to verify information are drawn to reliable sources. However, higher levels of trust in news organizations and close contacts were surprisingly linked to lower fact-checking rates, underscoring the influence of established trust relationships on information consumption.

The CIUS, focusing on sharing unverified information, found that approximately 14% of Canadians admitted to this behaviour in the past year. Regression analysis again highlighted age and education as influential factors. Older individuals were less likely to share unverified content, mirroring their reduced online engagement. Higher education initially correlated with increased sharing of unverified information, potentially due to a greater confidence in one’s ability to identify misinformation. However, this correlation disappeared when controlling for exposure to suspected misinformation, implying that education primarily influences the ability to recognize false content rather than the propensity to share it unchecked. Time spent online and prior exposure to misinformation both increased the likelihood of sharing unverified content, suggesting that increased online activity and familiarity with misinformation, regardless of accuracy, contribute to its spread.

Synthesizing the findings from both surveys, age and education emerge as key determinants of misinformation spread. While older individuals are less prone to both fact-checking and sharing unverified content, likely due to lower online engagement, the role of education is more nuanced. Higher education promotes fact-checking but also a potential overconfidence in identifying misinformation, leading to increased sharing of unverified content unless controlled for prior exposure to such information. These results emphasize the complex interplay of factors influencing online information consumption and underscore the need for caution in interpreting individual behaviours.

The study’s limitations include its reliance on self-reported behaviours, which can be subject to biases, particularly in the CIUS, where the response distribution was skewed towards not sharing unverified information. Furthermore, the surveys didn’t directly assess the accuracy of misinformation identification, leaving open the question of whether confidence in recognizing false content is justified. Future research should incorporate direct measures of misinformation identification accuracy and explore the sources individuals use for fact-checking, considering the potential influence of confirmation bias. By addressing these limitations, future studies can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complex dynamics driving the spread of misinformation and inform effective strategies to combat it.