The Partisan Battleground of Online Misinformation: A Deep Dive into Claims of Asymmetry

The digital age has ushered in an era of unprecedented information access, but it has also opened the floodgates to misinformation and disinformation. This phenomenon gained significant traction in the political arena during the 2008 US presidential election, marked by Barack Obama’s strategic use of social media. While Obama’s campaign leveraged social media effectively, accusations of manipulation and disinformation have plagued political discourse ever since. A recent study claims to have uncovered a partisan asymmetry in misinformation sharing, suggesting that one political side is more prone to spreading false information than the other. However, the methodology and conclusions of this study warrant closer scrutiny.

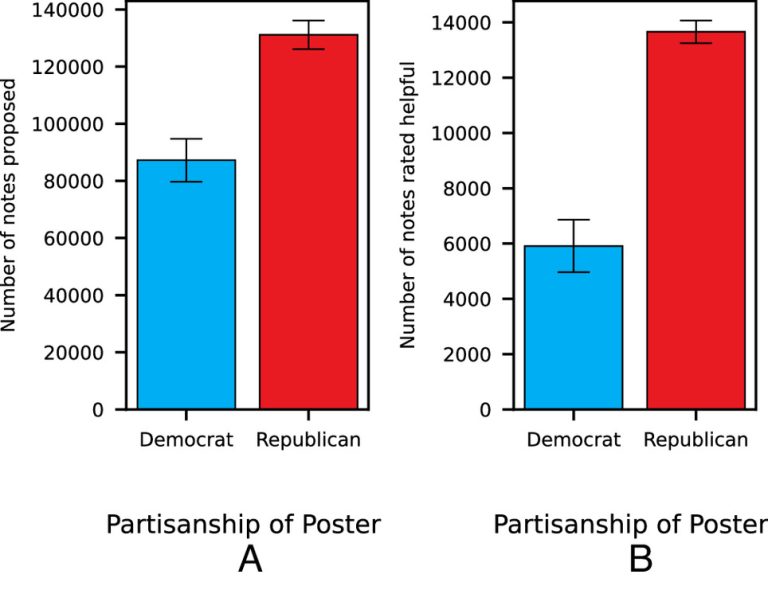

The rise of social media as a potent political tool continued with Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign. Trump, despite being outspent by his opponents, effectively utilized social media to mobilize his base and secure victory. This election cycle also saw a rise in allegations of election fraud, accusations that were mirrored in subsequent elections. The current landscape suggests that Democrats are regaining ground in the social media arena, actively utilizing features like Twitter’s Community Notes to flag content they deem misleading. The higher rate of Community Notes initiated by Democrats has been interpreted by some as evidence of greater misinformation dissemination by Republicans. However, this interpretation is simplistic and fails to account for potential biases in the flagging process itself.

The study, which analyzed tweets requesting Community Notes, highlights partisan divides in the types of claims flagged. Republicans frequently challenged economic claims made by Democrats, while Democrats were more likely to flag claims about tariffs. However, some of the examples cited in the study seem trivial and raise questions about the overall relevance to the issue of misinformation. For instance, the researchers note discrepancies in beliefs about the release date of a video game or the location of a photograph. While these examples might illustrate differing beliefs, they don’t necessarily constitute misinformation in the same way that false claims about economic policy or public health might. The study’s inclusion of such examples weakens its overall argument.

The core flaw of the study lies in its reliance on correlation without establishing causation. The researchers observe a correlation between political affiliation and the frequency of Community Note requests, but this does not inherently prove that one side is more prone to misinformation. The increased flagging could be attributed to a variety of factors, including differing levels of engagement with the Community Notes feature, varying sensitivity to potentially misleading information, or even strategic manipulation of the system for political gain. Similar correlations have been drawn in other areas, leading to misleading conclusions. The study’s methodology fails to account for these confounding factors, making its conclusions about partisan asymmetry questionable.

Furthermore, the study’s claim of objectivity is undermined by potential biases within academia and fact-checking organizations. The authors dismiss the possibility of political bias influencing their findings, but the very nature of research, particularly in socially charged areas, is susceptible to subjective interpretations. The composition of the research team and the selection of data points can inadvertently skew the results. The reliance on a “bridging algorithm” to account for bias, without providing details on its function or validation, further raises concerns about the study’s robustness.

The historical context surrounding health-related claims further complicates the issue. Many health concerns currently raised by Republicans, particularly regarding vaccines, were previously voiced by Democrats. For example, concerns about vaccine safety and potential links to autism were prevalent among certain segments of the Democratic Party. A comprehensive analysis should consider this historical context and avoid drawing conclusions based on a limited timeframe. The study’s focus on recent tweets without considering past trends overlooks the evolution of these narratives and the changing political affiliations of those expressing them. A more nuanced approach would involve analyzing these claims over a longer period and acknowledging the shifts in public discourse.

Ultimately, the study’s findings, while intriguing, are not conclusive. The observed partisan asymmetry in Community Note requests may reflect a variety of factors beyond a simple difference in propensity for misinformation. The study’s methodological weaknesses, including its reliance on correlation, limited timeframe, and potential biases, undermine its claim of objectivity. A more rigorous investigation, accounting for these complexities, is necessary to fully understand the dynamics of misinformation sharing in the online political landscape. The simplistic narrative of one side being inherently more prone to misinformation is not supported by the available evidence.