A Feast for the Eyes, a Meal for the Soul: Exploring the History of Image Consumption in ‘Iconophages’

Jérémie Koering’s "Iconophages: A History of Ingesting Images" delves into the intriguing and often bizarre history of consuming religious icons, a practice spanning from Ancient Egypt to the 20th century. This meticulously researched book unearths a wealth of historical examples, from drinking water that washed over magical stelae in ancient Egypt to the ingestion of ground relics in the Middle Ages. These practices, often aimed at healing or spiritual communion, reveal a complex interplay between the physical and the spiritual, offering a glimpse into the evolution of the human mind-body relationship across diverse cultures and eras.

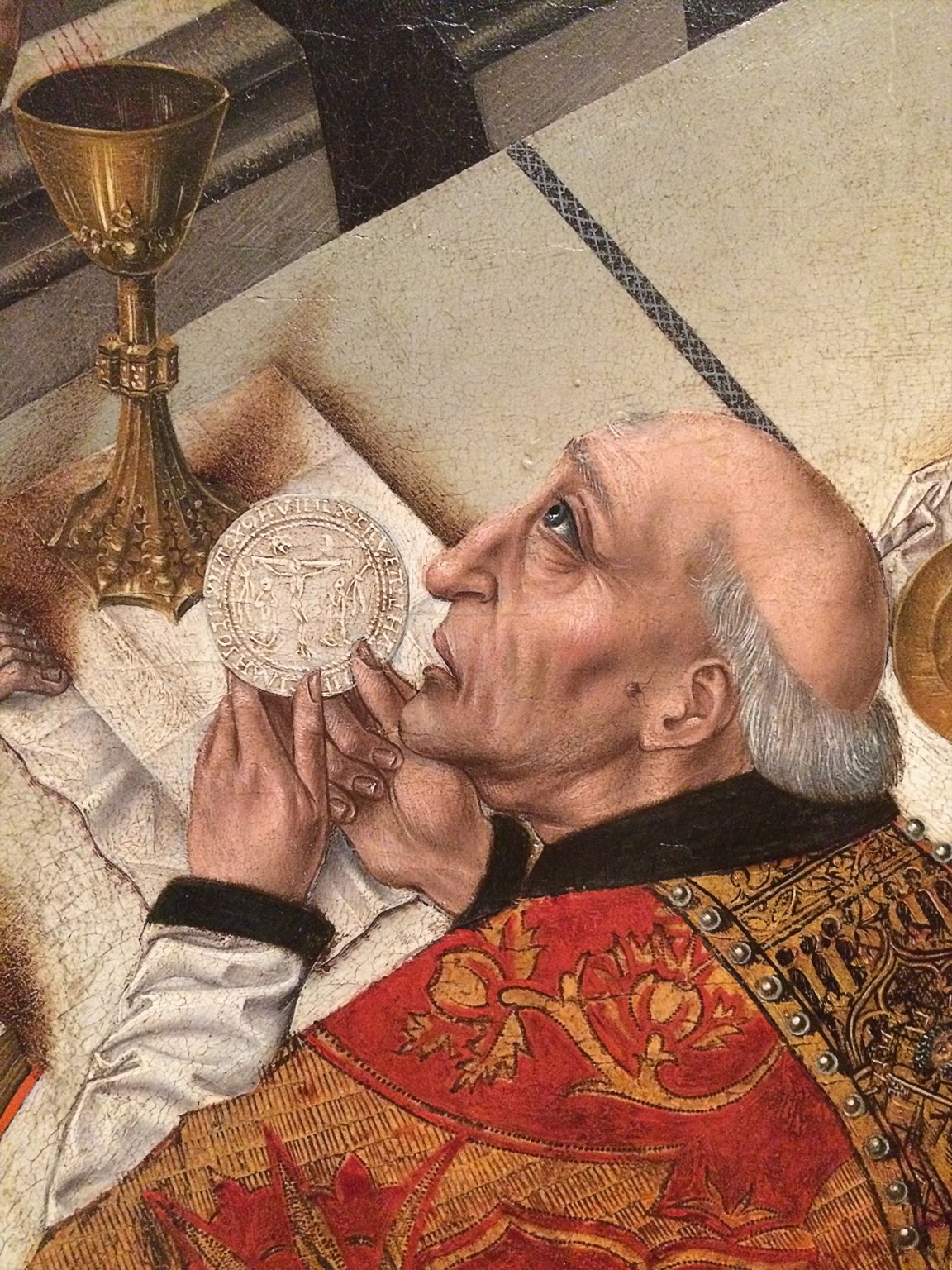

Koering’s central argument posits that in pre-Christian societies, magic and religion were inextricably linked. The act of ingesting an icon, a physical representation of the divine, was not merely symbolic but a means of establishing a direct connection with the sacred. It served as a ritual of belonging, solidifying membership within a shared belief system. This tangible consumption of the divine later evolved into symbolic rituals, exemplified by the Christian Eucharist, where bread and wine represent the body and blood of Christ. This symbolic transformation marks a significant shift in the relationship between humans and the divine, moving from physical ingestion to a more abstract form of spiritual communion.

While the premise is captivating, "Iconophages" can be a challenging read. The book is dense with detailed historical accounts, often overwhelming the reader with granular descriptions of specific rituals. Koering meticulously documents cases such as the use of water soaked in Thomas Becket’s bloodstained shirt to cure paralysis, or the placement of miracle-depicting woodcuts in the mouths of the deceased in hopes of resurrection. While these anecdotes are undeniably fascinating, the sheer volume of detail sometimes obscures the broader narrative and leaves the reader questioning the overarching significance of these practices.

Despite its density, "Iconophages" offers intriguing insights into the enduring human desire for connection with the divine and the persistent search for meaning and solace, often in the face of fear and mortality. The book’s exploration of these ritualistic practices reveals a recurring human tendency to seek tangible solutions to existential anxieties, even when those solutions defy logic or offer no demonstrable efficacy. The sheer variety of these practices across cultures and time periods underscores the universality of this human impulse.

The book’s relevance extends beyond historical analysis, offering a compelling parallel to contemporary society, particularly in the digital age. Koering’s exploration of ritualistic image consumption resonates with the current landscape of online interactions, where icons, logos, emojis, and memes function as modern-day totems, imbued with symbolic meaning and fueling fervent online communities. The rise of misinformation and conspiracy theories online echoes the pre-Christian fusion of magic and religion, where belief trumps evidence and irrationality holds sway.

Just as the ingestion of icons promised healing and protection in the past, today’s online echo chambers offer a sense of belonging and certainty in a complex and uncertain world. The fervent belief in conspiracy theories, the cult-like devotion to political figures, and the speculative frenzy surrounding meme-based cryptocurrencies all reflect the same underlying human desires explored in "Iconophages": the search for meaning, the yearning for connection, and the desperate hope for a quick fix to complex problems. Koering’s historical analysis serves as a cautionary tale, reminding us that such fervent beliefs, divorced from reason and evidence, rarely lead to positive outcomes. Instead, they often fuel division, conflict, and societal fragmentation, mirroring the historical consequences of religious zealotry and ideological dogma.