Supreme Court Ruling on Waqf Amendment Act: A Critique of Judicial Deference to Legislative Disinformation

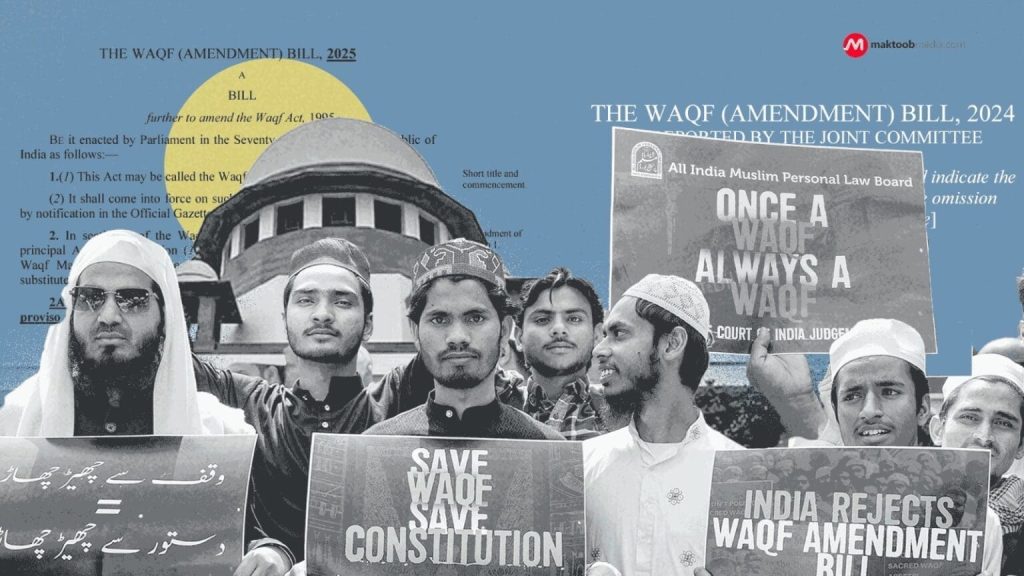

The Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, passed by the Indian Parliament, introduced sweeping changes to the governance of Waqf properties. These changes included allowing non-Muslim appointments to Waqf Boards, imposing a five-year Islamic practice requirement for Waqf creation, introducing stringent registration mandates, and abolishing the long-standing concept of “Waqf by user.” The government defended these amendments as necessary to address issues of opaque property management, unresolved land records, and to modernize Waqf governance.

Immediately following its enactment, the Amendment Act faced legal challenges in the Supreme Court, with petitioners arguing that it violated fundamental rights and constitutional principles of equality and separation of powers. They sought an immediate stay on the legislation, citing potential irreparable harm. An initial three-judge bench acknowledged key concerns and received assurances from the Solicitor General that no action would be taken on these issues pending further hearings. However, this provided only temporary relief, given the ambiguity surrounding the timeline and the lack of substantial reasoning. The case was later reassigned to a two-judge bench.

In September 2025, the two-judge bench delivered a 128-page judgment, upholding the Amendment Act almost entirely, staying only four provisions. This critique argues that the judgment is flawed because it fails to recognize the Amendment Act as a form of “legislation as disinformation,” a concept where law-making is based on a political narrative lacking empirical basis. This analysis proceeds in two parts: examining the Court’s reasoning on stayed and unstayed provisions and highlighting the judgment’s failure to address the law’s overarching expropriatory design.

Regarding specific provisions, the Court stayed the five-year Islamic practice requirement pending the formulation of rules to ascertain adherence. It also intervened decisively on Section 3C, which stripped government properties identified as Waqf of their status without judicial oversight. The Court held that the Waqf Tribunal, not an executive officer, possesses this authority. The stay on these aspects of Section 3C is crucial, as it addressed a central element of the Amendment’s expropriatory potential.

However, the Court’s acceptance of assurances from the Solicitor General regarding the appointment of non-Muslims to Waqf Boards, while seemingly pragmatic, sidestepped principled constitutional arguments. This reliance on executive assurances rather than engaging with fundamental rights concerns raises questions about the Court’s approach. Similarly, the Court’s “suggestion” that Muslim Chief Executive Officers be appointed “as far as possible” lacks the force of a mandatory injunction and provides room for circumvention.

The Court’s upholding of the abolition of “Waqf by user” and the mandatory registration regime, based on the argument that registration requirements have existed since 1923, disregards the petitioners’ concerns regarding historical Waqfs lacking formal deeds. This reasoning effectively defers to the legislature’s unsubstantiated claims about encroachment issues. The Court’s dismissal of expropriation concerns, citing the prospective application of the “Waqf by user” abolition, overlooks the law’s intricate implications.

A significant omission in the judgment is its failure to address the petitioners’ arguments regarding the Amendment Act’s expropriatory design. This scheme operates through multiple reinforcing mechanisms: adding hurdles to registration, allowing public objections to Waqf land records, and reducing penalties for alienating Waqf land. These mechanisms, when considered cumulatively, point towards a legislative intent to seize control of Waqf lands. The judgment, however, dismisses these concerns as mere apprehension. Furthermore, the prospective application of the “Waqf by user” abolition contains an exception that leaves historically undocumented Waqfs vulnerable to expropriation, particularly if challenged by government officials. The Court ignored arguments that similar concepts exist for other religious trusts and endowments, highlighting the discriminatory nature of the amendment’s impact on Muslim charitable trusts.

The Amendment Act places unregistered Waqfs in a precarious position. While ostensibly providing a six-month window for registration, the requirement of a Waqf deed for registration creates an impossible predicament for those lacking such documentation. The new process further empowers the Collector to challenge Waqf status based on claims of government ownership, stalling registration and denying unregistered Waqfs the right to legal recourse. The removal of protections for Waqfs registered via survey further exacerbates this vulnerability.

The government’s justification for these measures rests on a narrative of Waqfs as habitual land grabbers, based on questionable data. The claim of a “remarkable 116% rise in Waqf area” is attributed to encroachments, despite being more likely due to increased documentation of pre-existing Waqfs on the newly established WAMSI portal. Inconsistencies in government data, highlighted by the AIMPLB, further undermine this claim. Similarly, the JPC report’s data on “encroachment” lacks clarity and methodological explanation, rendering it unreliable. Finally, the government’s reliance on three isolated cases to demonstrate the link between “Waqf by user” and land grabbing is demonstrably weak.

The Supreme Court’s deference to the legislature in this case is problematic. While the presumption of constitutionality is a fundamental principle, it should not shield legislation based on a demonstrably flawed and discriminatory narrative. The Court’s reliance on this presumption, coupled with its acceptance of executive assurances, serves to legitimize the government’s divisive rhetoric. The Court could have utilized the principle of balance of convenience, considering the potential irreparable harm to Waqf properties, to justify a more comprehensive stay on the Amendment Act.

This judgment leaves affected communities in a state of uncertainty, raising concerns that this uncertainty may solidify into a legal fait accompli. The Court’s failure to critically examine the government’s manufactured crisis and its underlying discriminatory narrative represents a missed opportunity to safeguard fundamental rights and uphold constitutional principles.