The Perils of Systematizing Deception: Why Traditional Approaches Make States More Vulnerable

A recent report by the New America think tank on "The Future of Deception in War" has sparked controversy by advocating for a systematic approach to military deception. While the report offers detailed frameworks and proposes the establishment of dedicated deception doctrines and staffs, critics argue that this approach fundamentally misunderstands the nature of deception and risks making states more vulnerable. They contend that deception, like jazz improvisation, cannot be bureaucratized and that the very act of systematizing it renders it ineffective. The report’s emphasis on planning, integration, and measurable outcomes clashes with the improvisational, opportunistic, and often chaotic nature of successful historical deceptions.

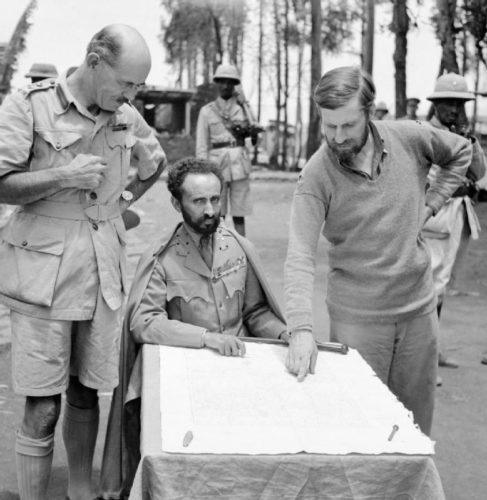

The core flaw of the report, critics argue, lies in treating deception as a problem to be solved through engineering-like methodologies rather than as a dynamic art requiring human intuition and adaptability. They point to historical examples like the Haversack Ruse at Beersheba, Ethiopia Mission 101, Operation Bertram, and Operation Mincemeat, all of which succeeded due to their improvisational nature and exploitation of enemy assumptions. These deceptions were conceived and executed with a keen understanding of the specific context and the enemy’s psychology, something that cannot be captured in standardized doctrines or procedures. These historical examples all utilized a "seed set theory" of an unshakeable core of truth, surrounded by improvised supporting lies, spread by a credible influencer.

The report’s recommendations to "ensure approaches are credible, verifiable, executable, and measurable" and to prioritize security with strict need-to-know criteria are precisely the opposite of how effective deception operates in reality. Real deception thrives on ambiguity, unverifiability, and wide dissemination to create an aura of authenticity. It’s about exploiting the enemy’s expectations and operating outside established norms, including one’s own. The rigid structures proposed by the report would stifle creativity and adaptability, the very qualities essential for successful deception.

Furthermore, the report’s focus on AI-powered deception systems is seen as another misstep. Critics warn that complex technological solutions create single points of failure, making deception efforts vulnerable to compromise. They emphasize the importance of human insight and psychological understanding over technological sophistication, citing historical examples like D-Day’s Operation Fortitude and the Midway intelligence breakthrough, which relied on astute analysis of the enemy’s mindset. Simple human lies, adaptable and easily modified when exposed, are preferred over elaborate technological fabrications that crumble under scrutiny.

The report’s analysis of Ukrainian and Russian deception tactics also raises concerns, as it overlooks the possibility that the authors themselves might be targets of deception. The authors’ detailed explanations of deception techniques, critics argue, demonstrate a lack of appreciation for the nuanced and often opaque nature of their subject. True practitioners understand that revealing their methods undermines their effectiveness. This report, paradoxically, advocates for the very capabilities its existence jeopardizes.

Critics propose an alternative approach to military deception, drawing lessons from domains like poker, con artistry, and intelligence operations in denied areas. They advocate for continuous, small-scale deception operations ("stay always hot"), rapid adaptation and learning from failures ("fail fast"), and testing deceptions against real adversaries in real-world scenarios ("test in production"). Embracing uncertainty and utilizing distributed, loosely-coupled deception efforts ("microservices over monoliths") are also recommended, as opposed to grand, centralized schemes vulnerable to catastrophic failure. The fluidity and adaptability of these strategies offer a more resilient and effective approach to deception in the complex and ever-shifting landscape of modern warfare.

The success of Ukrainian deception efforts, often cited in the report, is attributed not to sophisticated planning but to a cultural comfort with improvisation and an institutional tolerance for failure. Ukrainian tank commanders, for example, are known for their constant, creative lying without seeking permission, readily adapting their tactics as needed. This adaptability, rooted in human judgment and operating outside rigid institutional processes, is difficult to replicate through systematic approaches. It highlights the importance of fostering a culture that values initiative, risk-taking, and rapid adaptation.

The report’s authors warn against deceiving ourselves into thinking that change is not needed. Critics agree, but they argue for a different kind of change. Instead of building a "Maginot Line" of deception doctrine, they advocate for institutional agility and adaptability, mirroring the operational flexibility of Orde Wingate’s Chindits during World War II. In a world rife with deception, the advantage lies with those who can adapt most quickly when their deceptions are inevitably exposed. This requires a shift in military culture, valuing improvisation, risk-taking, and a deep understanding of foreign cultures over rigid adherence to doctrine and technological solutions.

The report’s recommendations are characterized as the "militarization of management consulting," offering sophisticated-sounding solutions that fail to grasp fundamental realities. By treating deception as an engineering problem rather than a human art, the report fosters a dangerous overconfidence while increasing vulnerability. True military advantage in the realm of deception comes from institutional agility, enabling effective operation in an environment saturated with misinformation, where everyone is lying to everyone else, including themselves. This requires a fundamental shift in approach, prioritizing human adaptability and cultural understanding over rigid doctrines and technological quick fixes.

Instead of focusing on elaborate deception doctrines, military institutions should prioritize cultural adaptation, fostering an environment that embraces failure, improvisation, and calculated dishonesty. This necessitates reforming personnel systems that penalize risk-taking. Investment should be directed towards educating individuals to understand foreign cultures deeply, enabling them to craft believable lies, rather than relying on technologies that attempt to automate deception. The emphasis should be on building rapid feedback systems that quickly identify the effectiveness of deception efforts and promote continuous adaptation, not on complex planning systems that stifle creativity.

Operational security should be achieved through simplicity, employing hard-to-detect deceptions rather than resorting to complex, vulnerable technological solutions. Finally, it’s crucial to embrace the inherent uncertainty of deception, acknowledging that it cannot be fully measured, systematized, or controlled. This uncertainty is not a flaw but a characteristic of deception’s dynamic nature. A truly effective approach must be comfortable operating in the gray zone between truth and falsehood.

Military institutions must move away from the rigid, systematized approaches advocated by the report and embrace adaptability, improvisation, and a deep understanding of human psychology. By fostering a culture of calculated risk-taking and valuing human intuition over technological quick fixes, they can achieve true agility in the face of deception. This will enable them to operate effectively in the ambiguous and ever-shifting landscape of modern warfare, where the ability to adapt quickly and creatively when deceptions are exposed is the key to maintaining the upper hand. The Maginot Line mentality of building elaborate defenses against past threats must be replaced with the flexible, adaptive mindset of the Chindits, ready to navigate the uncertainties of a world saturated with misinformation. Only then can states hope to not only survive but thrive in the age of deception.